It is difficult today to believe that a person’s courage or ability in conflict can be affected by the colour of their skin, but that has not always been the case. Given North America’s history of slavery and subsequent emancipation, many have believed, and continue to believe, that those races so enslaved were lesser persons and that their abilities to conduct themselves with distinction in the face of battle were less than others. Let’s be blunt, we’re talking about white versus black soldiers and the inherent racism that exists generally in the public consciousness and specifically in the armed forces.

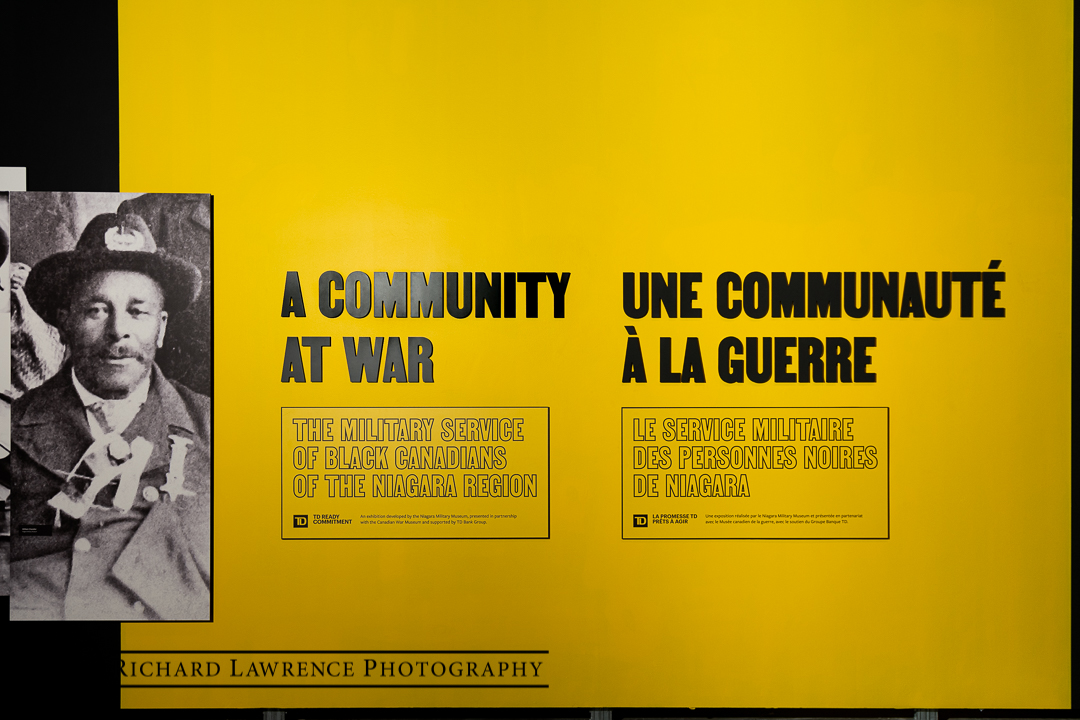

But the Niagara Military Museum has never believed that Black soldiers didn’t deserve the same recognition as every other soldier. They have, within the walls of their Museum, a section devoted exclusively to Black Military History specifically detailing the exploits of Black soldiers from the Niagara region dating from the American Revolution to current times. It is this display, titled “A Community at War”, that Dr. Tim Cook (Director of Research and Senior Historian with the Canadian War Museum and Curator of this exhibit), in partnership with the Niagara Military Museum, has brought to the Canadian War Museum. Wilma Morrison and Pastor Lois Dix were the driving forces behind this exhibition for the Niagara Military Museum but, unfortunately, Ms. Morrison died of Covid-19 in 2020.

In a series of plaques, one can trace some of the battles in which black soldiers from the Niagara region have distinguished themselves and been awarded medals, including the Military Medals for bravery. One could spend pages detailing the exploits of each of the individuals named in the plaques but that would defeat the purpose of going to the Museum and seeing the display for yourself. Suffice it to say that the display is in chronological order starting with Richard Pierpoint, born in Senegal around 1744 and captured as a slave at 16 years old. The British offered freedom if slaves fought against the American Colonies so he joined and fought with Butler’s Rangers (a Loyalist regiment in upstate New York) and in 1784 was awarded a land grant of 200 acres. In the War of 1812, Pierpoint petitioned for an all-Black unit and a Coloured Corps was created under Capt. Robert Raunchey, distinguishing itself in the Battle of Queenston Heights.

As hard as it is to believe, Canadian (then British) Blacks from the Niagara region went to fight in the American Civil War, which was particularly dangerous due to the “Fugitive Slave Act” of 1850 which dictated that all escaped slaves, upon capture, would be returned to their owners and was in effect in not only the southern states but also the northern “free” states. Of about 40,000 Canadians (British) who served in the Union Forces, it is believed that about 2,500 were black.

World War I saw very distinct racism in that Black Canadians who rushed to volunteer to fight were turned away at the recruiting stations. When Arthur Alexander queried the Minister of Militia and Defense on why this occurred, he was informed that acceptance into units was up to the Commanding Officers of the units in question and that there was no nationwide reason or policy to exclude Blacks. However, the Chief of the General Staff, Major-General W. Gwatkin, in a memorandum dated 13 April, 1916, indicated that he felt that the “negro was vain and imitative … not impelled to enlist by a high sense of duty … not likely to make a good fighter…”. It would be hard to overcome this mindset from the very top but Gwatkin did suggest that perhaps that Blacks would be suited to a labour unit and this may have been the genesis for the 2nd Construction Battalion, the first and only all-Black battalion in Canadian military history, which worked under the Canadian Forestry Corps during WWI. Also, the Canadian Expeditionary Force usually recruited locally but the 2nd was recruited nationally and 22 Blacks from the Niagara region joined. In fact, the 2nd Construction Battalion had about half of the 1300 – 2000 Canadian Black soldiers who joined in WWI, the rest being accepted into standard military units.

Now, before moving on, I’d like to just say a quick word about the importance of logistics to an army and point out that the 2nd Construction Battalion and the Canadian Forestry Corps were integral to the movement of the great armies then in battle. They were, in part, responsible for logging, milling, and shipping timber as well as helping to replace bridges destroyed by retreating armies, improve roads and a logging railway. The lumber was used in revetting trench sides, make duckboards to walk on in the muddy trenches, ammunition boxes, gun platforms, and anything made of wood. Without these contributions, the Allied armies would have had it much worse. If one doubts the importance of logistics, please refer to Napoleon’s march on Moscow, Hitler’s invasion of Russia, Rommel’s war in North Africa, or countless other battles in which extended logistics lines caused the failure of the attack. Although the work was “just” manual labour and unexciting, it provided a necessary service to the successful defeat of the enemy.

There were, as mentioned, Black soldiers in regular units as well, such as James Grant, who, in 1918, was the first African-Canadian awarded the Military Medal, or John Bright, awarded the Military Medal in April, 1918, at Passchendaele for “… exceptional courageousness and rendered exception service…”.

There are other stories that need to be told as well. In World War II, there are stories of those who did not come home from the war, of Loyst Kelly, Canada’s first Black paratrooper, along with Cleland Henson, and Clarence Lapierre. There are also stories of families who had more than one member join up such as the Brown sisters (Connie and Kathleen) and the Johnson brothers (Douglas, Clarence, Beverly, and David). And more recently, there is acknowledgement of MCpl. Stephen Thomas, awarded the Medal of Bravery for action during his second tour in Afghanistan.

One cannot generalize about any one group of peoples based on a single trait such as skin colour. There are hundreds of examples of fighting non-white groups such as the Zulus (Isandlwana), the Gurkhas, Indian Sepoys, Indigenous Nations, Maoris, etc., all who have brought distinction and honour to their countries or cultures. One should remember upon viewing this exhibition that it illustrates the willingness and courage of Black Canadians to answer the call of country from only one small region of Canada – Niagara. Extrapolate that desire to every region within Canada and you have a fighting force and history of which anyone can be proud. The exhibit is at the Canadian War Museum until 8th May, 2022.

To see all the pictures, Click Here: