Operation Nanook, in general, is a sovereignty operation conducted annually during the summer in Canada’s north to provide the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) the opportunity to assert Canadian sovereignty in the north, demonstrate and enhance the CAF’s ability to operate in the harsh northern conditions, and to train and assess emergency operations preparedness. To that end, Op Nanook 2017 adopted a two pronged approach to meet these requirements by engaging in two separate exercises in two separate areas of Canada’s north: Labrador and Rankin Inlet, Nunavut. In Labrador the CAF underwent sovereignty and defence exercises that also provided training for northern operations while in Rankin Inlet the primary focus was on emergency preparedness in a Whole-of-Government (WoG) scenario while also taking the opportunity to conduct land training. DND invited media to embed journalists into both operations with the troops from the 12th – 27th August but this article focuses on the much shorter overview of the emergency preparedness exercise at Rankin Inlet that the media was invited to oversee during the 23rd/24th August, 2017.

As an adjunct, Rankin Inlet is a forward operating location (FOL) for NORAD and as such operational security (OpSec) prohibited the taking of any images that showed any portion of the FOL, including the inside of hangers, empty or not (one happened to have CAF elements up for northern training and housed on cots in the hanger), any operations centres within the FOL, any assets not directly involved in Op Nanook (such as a civilian helicopter), or even the fence surrounding the FOL.

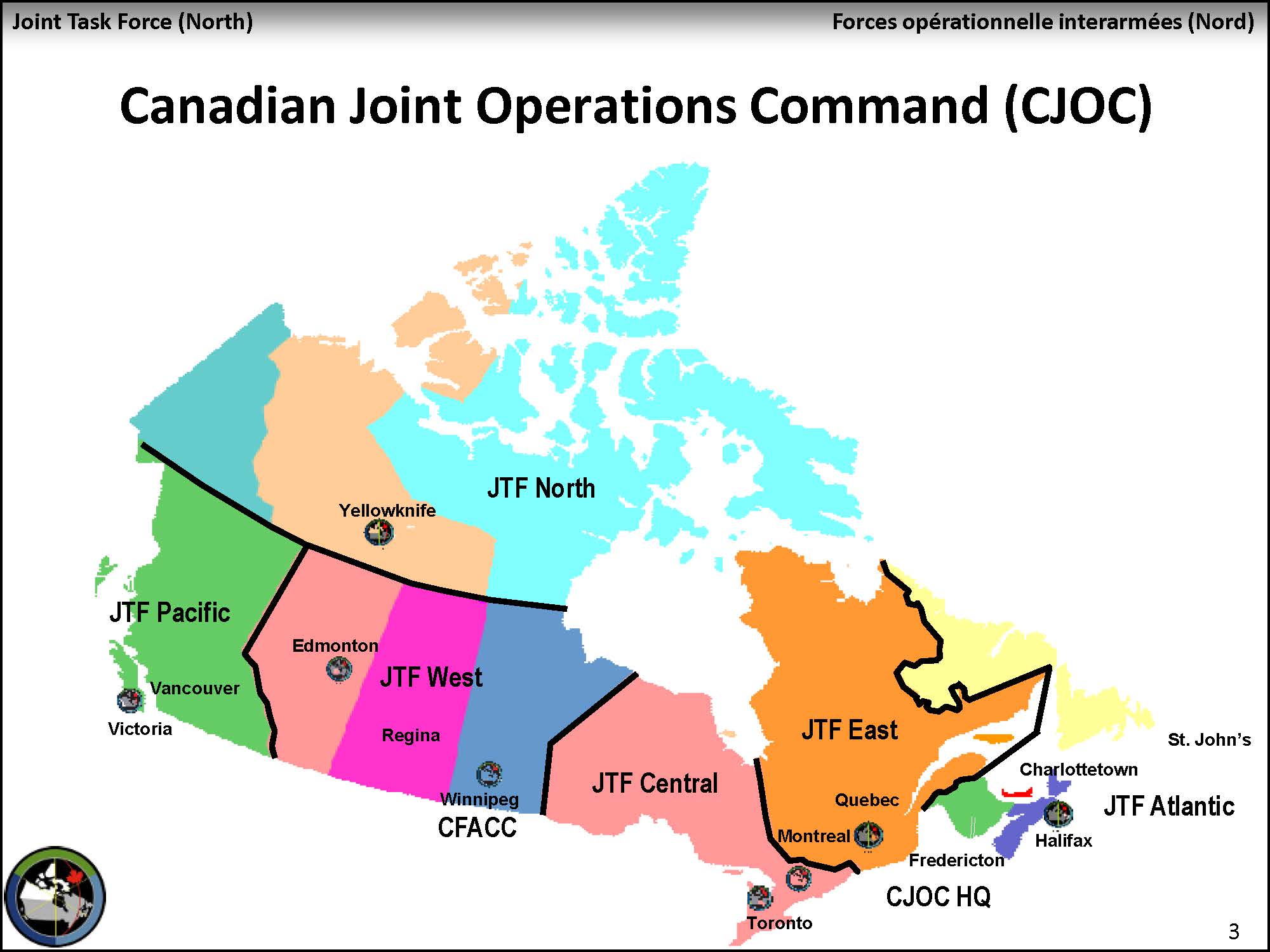

As with any military operation, it’s necessary to have an overview of the participants and their organization so that their upper level goals are clear and then the lower level exercises can be assessed in meeting those criteria. In order to do that, one needs to understand the Joint Task Force organizations.

If you are just looking for pictures, all the pictures from Op Nanook 2017 are here, including landscapes and non-op pictures.

TASK FORCES

The Canadian Joint Operations Command (CJOC) comprises six Regional Joint Task Forces (RJTF), and Joint Task Force North (JTFN) is the RJTF supporting operations in Canada’s three northern territories. The stated purpose of the RJTFs is “ … maintain a continuous watch over Canada’s land mass and air and maritime approaches … and keep the CAF aware of security threats and other concerns in or approaching Canadian territory, including the North”1. To be more specific to JTFN, their mission is to “exercise sovereignty and contribute to safety, security and defence operations in the Canadian North” (BGen Nixon, Commander JTFN)2. Operation Nanook is one of a set of annual, recurring operations to satisfy these missions.

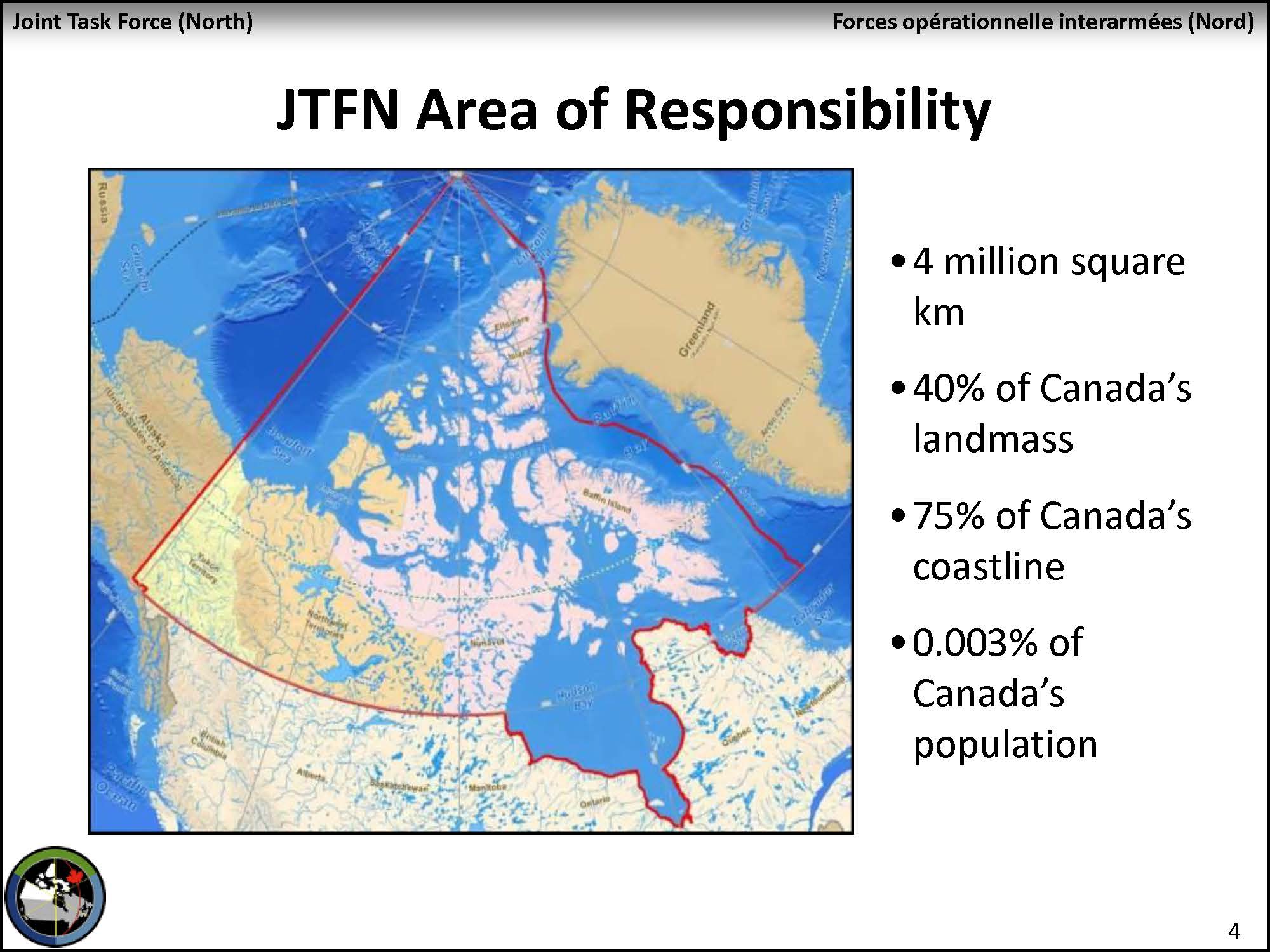

JTFN is the largest of the six RJTFs comprising 75% of Canada’s coastline, 40% of her landmass, and a grand total of .003% of her population. JTFN does not have large numbers of forces to be deployed but formulates and executes plans utilizing their meagre resources augmented by forces from the south. There is a command organization in Yellowknife with small detachments in Whitehorse, Iqaluit, and Rankin Inlet along with the 1st Canadian Ranger Patrol Group (1 CRPG) and the Junior Rangers (a sub-set of the 1 CRPG, under 18 years old, not supported by the CAF but supported by 1 CRPG). They are supported by 440 Transport Squadron of four CC-138 Twin Otter aircraft based in Yellowknife.

To be clear, many of JTFN’s goals stress the defence of Canada’s north. In a briefing by Maj. Conrad Schubert, J9 Civil Military Cooperation, JTFN, he stated that regarding the missions of JTFN “the one at the top [defence] is the least likely. There is no assessed military threat to the north”3. That doesn’t mean the CAF doesn’t prepare for the defence of the north, all it means is that they are training for a mission that is not an immediate threat. So, what is the immediate threat?

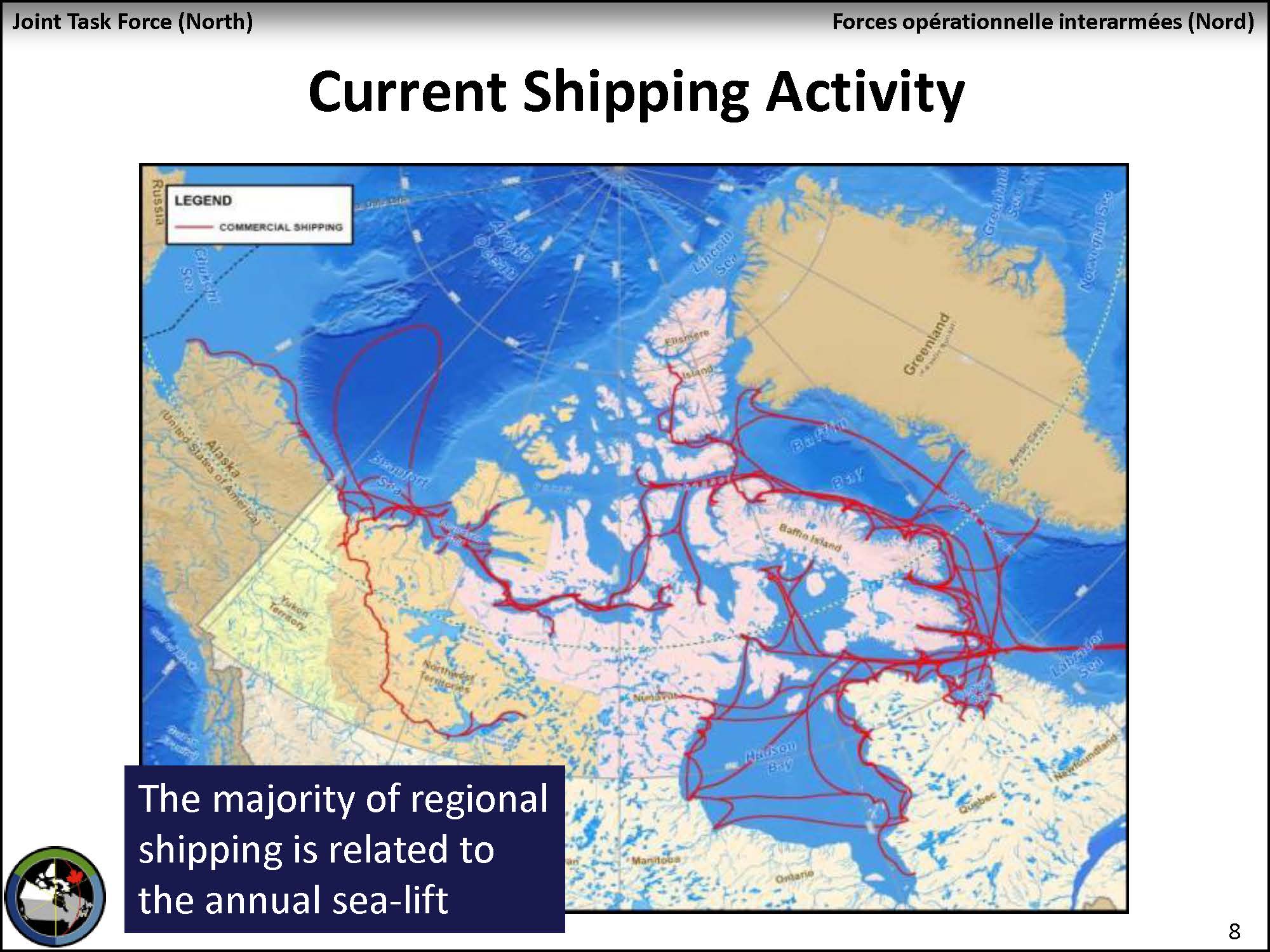

One threat is a growing activity and interest in the north created as global warming melts the ice pack and opens up once unnavigable shipping routes. This simple fact has people worried that countries will use the North-West Passage (NWP) for transit and the potential for catastrophic environmental damage. If the shipping is ore and it sinks, then the damage is minimal and the cargo just becomes rocks on the bottom, however, should it be oil, the magnitude of the problem exceeds imagination.

Now, part of this issue was addressed by Maj. Conrad Schubert in a media briefing at Rankin Inlet during Op Nanook 2017 when he stated that so far there have been less than 300 transits of the NWP in history and of those, only a few were of a commercial nature. Of those, they were accompanied by Coast Guard and ice breaking vessels to make sure nothing untoward happened and the exercise was done more to show that it could be done rather than done economically. The current costs involved make commercial shipping through the NWP economically unviable at the moment.

Where it might become viable is through the Russian north where the idea is to make shipping more efficient from Asia to Europe. Russia has a large population in its north and an infrastructure to support it, including ports which make transiting through the Russian north more attractive, commercially, than through Canada’s NWP which has no infrastructure at all.

Another issue is the navigability of the NWP now that the ice is melting. Again Maj. Schubert suggested that the ice breakup is more of a problem than one would think. The ice mass needs to be considered in two parts: sea ice and land-fast ice. The sea ice melts and reforms each year but the land-fast ice is attached to land masses and grows each year until it becomes very thick. It is the land-fast ice that is breaking off now and is carried by the wind and currents into the NWP where it becomes a hazard to navigation, i.e. hit it and you sink. Recent statistics indicate that a ship transiting the NWP has an 85% chance of not hitting anything BUT, if that ship doesn’t have an ice hardened hull and does brush against the ice, it’s going down.

So, the big take-away from this is that Canada doesn’t have an assessed immediate military threat from the north nor does it seem likely that commercial traffic through the NWP is going to be a problem in the near future. However, there is still a big shipping issue with annual sealift to northern communities.

If one looks at a map of our northern territories, moving from west to east, one will notice that the Yukon has a comparatively good road system and in concert with that infrastructure follows power and communications lines. This means that hydro-electric power can be established in one location and transported to other parts of the territory and that population centers have hardline communications between them. In the North-West Territories the number of roads diminishes somewhat and the amount of hydro power/communications that can be distributed is correspondingly less.

Looking at Nunavut one notices that there are no roads interconnecting population centers and hence no ability to provide power or communications infrastructure between settlements. This means that even if hydro-electric power was available, there is no way to distribute it. The same with hardline communications in that from an inter-city perspective, there is none. Almost every population center in Nunavut is isolated and totally dependent on diesel generated power (and has been since the 1970s) and communications through satellite. To survive, all the diesel fuel required by a settlement must be transported by sealift during the navigation season prior to ice forming and along with that all the supplies required by the settlement to last out the winter months. And their winter starts earlier and lasts longer than in the south. If they don’t get the supplies delivered prior to the ice forming, then they are on their own. Although these settlements are highly resilient, they are also extremely vulnerable to any disruption in supplies, either from sealift issues or issues of off-loading the supplies. Such is the focus of Op Nanook in Rankin Inlet this year.

OP NANOOK 2017 – RANKIN INLET

At Rankin Inlet, Op Nanook 2017 “focused on the full range of crisis response and consequence management activities resulting from an overwhelming emergency in an isolated community, engaging multiple tiers of government and partners including the Canadian Armed Forces”4. Basically what this means is they introduced a crisis into the community and then let the community deal with it as a learning exercise. The crisis was of such a magnitude that they had to engage in a whole-of-government (WoG) model to mobilize local facilities, territorial agencies, federal agencies, and, as an element of last resort, the CAF, collaborating across the federal family to make use of available resources

Some of the partners involved in this exercise are the RCMP, Public Health Agency of Canada, Indigenous and Northern Affairs, Government of Nunavut, DND, Agnico Mines, Nunavut Emergency Services, Nunavut Health Services, and a host of other agencies. As stated by Maj. Schubert “None of us has enough stuff to do everything and we the military are not the agency to solve any crisis, we are the agency of absolute last resort. After us is … chaos – literally”5.

The simulation was created by the Canadian Army Simulation Centre (CASC) working since February with all the local, territorial, and federal organizations involved determining what it was they needed to get out of the exercise. Additionally there was a corporate player involved, the Agnico Mine, who showed immense interest in being involved in the disaster scenario because if they had a problem, they would look to the town for help and hoped that if the town had a problem, they would ask Agnico Mine for help. Agnico actually had two people participating in the Emergency Operations Centre (EOC) as part of the exercise.

To set the scene, Rankin Inlet is a hamlet of approximately 2,900 people located 470 kilometres north of Churchill, Manitoba, on the north-west shore of Hudson’s Bay, without any external access other than an airport and the annual sealift which has a one month window. There are approximately 300 CAF personnel in the area conducting annual training since 14th August. Survival of this community and the Agnico Mine depends on the summer sealift of fuel and supplies.

22nd August, 2017

The exercise started on the 22nd with a call to the fire department that a supply barge was on fire at the unloading dock. While the Fire Chief was aware it was a drill, the fire fighters were not and went in expecting the worst. When they arrived there was a simulated fire to put out and simulated casualties to deal with. The fire was extinguished and nine casualties were taken to the hospital which has a capacity of 12 significant cases. So, the first part of the exercise brought local resources into play by stressing the fire department, EMS, and hospital and at the same time damaging the barge unloading area and stopping supplies from landing. At some point, the first responders were overwhelmed and the territory declared a public emergency, triggering requests for assistance at the federal level.

23rd August, 2017

On the morning of the 23rd, the fire reignited itself with an explosion and fire causing further damage to the barge unloading area making it unusable. Because of the chemicals, petroleum, oil, and lubricants on-site, the fire created a toxic plume of smoke which drifted to the north-northwest creating a public health hazard and resulted in closing the airport (no airlift available now for supplies/personnel or to fly out the injured) and possible contamination of the water supply which the toxic cloud was passing over. What this created was a mass casualty crisis for the hospital in that they gained another fourteen casualties with chemical burns as well as normal fire fighter injuries, the possibility of toxic inhalation issues as well as now being over capacity. As part of the exercise they setup a triage tent in the hospital parking lot but as resources were past capacity they contacted the Public Health Agency of Canada to have a National Emergency Strategic Stockpile (NESS) mini-clinic deployed which was ferried up by the RCAF (obviously ahead of the smoke plume closing down the airport for exercise purposes).

NESS is housed within the Public Health Agency of Canada’s Centre for Emergency Preparedness and Response and is a stockpile of medical supplies, drugs, and equipment to be deployed within 24 hours in support of health emergencies anywhere in Canada. One of the key components is the Mini-Clinic which is a scalable medical unit that can be deployed, usually within 24 hours, and setup in any convenient empty building. Its purpose is to provide additional support to EMS for triage and basic treatment such as one would expect in a walk-in clinic. As part of Op Nanook, a mini-clinic was deployed in Rankin Inlet, and while not used during the exercise (they did a table-top exercise rather than actual exercise with people), it was absolutely necessary to go through the deployment to identify any issues deploying to the north.

The emergency operation centre (EOC) now looked at setting-up shelters, transporting residents, and feeding them after going door-to-door to get residents to evacuate their homes. While they were able to do the individual notifications as a drill, no-one was actually evacuated.

24th August, 2017

On the morning of the 24th, a gastro intestinal infection was introduced at the shelter and there was a missing family, presumed to be out on the land, that generated a ground search and rescue operation (GSAR) involving the Canadian Forces troops training on location with 1 CRPG. The GSAR was co-ordinated with the local authorities and then the Rangers took the lead in organizing and directing the search with three columns of ATVs manned by CAF and Ranger troops.

It should be noted that at no time was the military in charge of anything other than their own troops. In this type of scenario the military plays a supporting role only, subordinate to the local authority as are the territorial and federal agencies, and is usually brought into play once a Request For Assistance (RFA) has been communicated to DND. However, if the on-site commander determines that there is danger to life, they may provide assistance without having to go through the chain of command before taking action.

The disaster caused a lot of damage and destruction (simulated) to the community (especially the unloading dock), the loss of much of the town supplies for winter, and the mine lost a lot of winter supplies resulting in the question “What do we do next? What are the consequence management issues?”. The continuing part of this exercise will be spent answering those questions because this is life-threateningly serious once the freeze-up begins and no more barges are able to come up.

Military Training

On the training side of the Op Nanook, there were approximately 300 troops in the area participating in training exercises, primarily reservists of the Arctic Response Company Group (ARCG). The ARCG is made up of a series of mostly southern units, of which most come from 38 Canadian Brigade Group (38 CBG), headquartered in Winnipeg and augmented with troops from about 35 other units, along with the 1st Canadian Ranger Patrol Group (1 CRPG). Exercises consist primarily of training with the Rangers and learning how to live off the land and work in the north. The troops had to ruck out to a survival site and sleep under the stars, build shelters, identify edible plants, and learn to catch, gut, and cook fish on a stone fireplace, etc. In other training, they were taught how to use four wheeled All-Terrain Vehicles (ATVs or quads) out on the land and how to do a GSAR using ATVs. Cpl Heidi Schulz, a medic with 15 Field Ambulance (Edmonton) could only say that:

“The training with the Rangers has been fantastic. It’s stuff you’d never get to learn and do on your own. The traditional fishing, the learning about berries and other plants and whatnot … or just … remedies.”6 and “ … having a great time… it’s a lot of firsts. First time catching and eating arctic char, first time caribou, muskox, … the local food they’re bringing in for us is just awesome as well.”7.

During the time of this visit, the troops had relocated back to the Rankin Inlet FOL to participate in the disaster exercise and, in some cases, acted as observers providing insight only when it was clear that the local participants were reaching the end of their resources. Some also got to play the victims of the fire/explosion and were made up with simulated injuries that looked more than real, and were then coached on how to act when brought into triage.

During one of the periods where the troops weren’t required, they were put on assault boat training using Ridged Hulled Inflatable Boats (RHIBs) in the water behind the accommodation blocks. Here they learned to work as a team in paddling and maneuvering the RHIBs. The highlight of the day, for those not participating, was the man overboard drill and the capsizing drill which had the troops purposely flip the boat over, dumping everyone into the COLD water and then organize themselves to flip it right side up again, all in a matter of minutes.

On the next day, as part of participating in the emergency response, some of these reservists were put to work using their new skills in GSAR with ATVs searching for the missing family out on the land. Again, acting upon a request from the local authority, the Rangers and CAF troops evaluated the most promising areas, separated into three columns of ATVs, and sped off into the tundra.

So, the hamlet had a disaster drill involving all levels of government and have a lot of evaluation to do in the weeks and months going forward but the exercise can be deemed a success, not only in what it showed worked, but in what it showed could be improved. The military had northern training and inter-operated with civilian authorities and multi-tiers of government to achieve a successful outcome. Overall, the broad goals of Op Nanook 2017 seem to have been achieved. But can more be done to show presence, surveillance, sovereignty, and defence in the north?

There are many programs for additional assets in the north. Polaris is proposing the RAMPAGE two-seat tracked vehicle to replace the BV206 (carries 10). The Artic Offshore Patrol Ship (AOPS) will allow the RCN to operate 3 seasons in the arctic and will have other capabilities for research, Canadian Border Services, RCMP, Fisheries and Oceans, etc. A winterized Argo Amphibious Vehicle may replace the existing ATVs or at least supplement them. The Polar Epsilon project should provide better imagery for surveillance and weather requirements using the RADARSAT-2 earth observation satellite and whose data will be shared with other agencies. Thought was given to increasing the number of Rangers but this is not really possible as they are already close to 2% of the population, which is a very high percentage. The Rangers are, however, in line for new equipment and clothing.

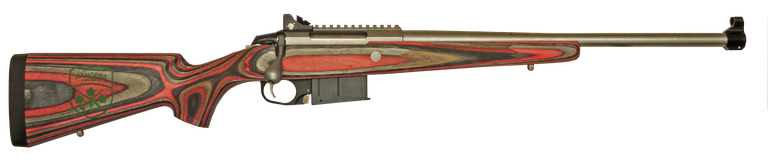

The Rangers have been using the bolt-action Lee Enfield No. 4 rifle since 1948 and this rifle is going to be replaced by the licenced-built variant of the Swedish-designed Tikka T3 CTR bolt-action rifle – the Colt C-19. There was discussion in the 1980s and 1990s about replacing the Lee Enfield with a .223 calibre rifle but the Rangers:

“… were not the least bit interested in that. That was not something that pleased them in any way. …The rifle is issued to them not so they can shoot hordes of invading enemy. It’s so they can protect themselves. The things that they want to protect themselves from don’t die when you shoot them with a .223 – you need something a little more powerful”8 (Maj. Schubert).

The C-19 is .308 calibre and is ballistically very similar to the Lee Enfield .303 calibre. It has a stainless steel barrel as opposed to blued steel and won’t rust. The laminated stock is superior to the old solid piece stock in that in won’t warp when it gets wet. The C-19 has a 10 shot magazine and costs about $2,000 per rifle. The old Lee Enfield will be gifted to those Rangers who possess a proper firearms acquisition certificate rather than collect them all for destruction.

During the three day Op Nanook emergency preparedness exercise (22nd – 24th August) the hamlet, the territorial government, and the federal government had to have a high-level of communications and co-ordination to achieve a favourable outcome. Given that everyone realized just how life-and-death a situation like this can be in the north it looked like egos and political fiefdoms were put aside for the common good of the people of Rankin Inlet. Hopefully further analysis of the exercise and the follow-up analysis will provide a foundation roadmap for handling disasters in the north.

The military training portion of Op Nanook was successful on several fronts. First, it continued to show the Canadian presence in the north although one could also say that these permanent northern settlements and 1 CRPG satisfy that criteria on their own without the addition of CAF personnel. Putting the CAF troops out on the land with the Rangers definitely helped make the troops more self-reliant in a harsh and unforgiving environment as well as teaching them new personal skills along with their ATV, GSAR, and RHIB training. So, success all around.

My thanks to Esprit de Corps Magazine for putting my name forward for this quick trip and to DND for providing the transport, rations, and quarters, as well as the opportunity to observe, even in this limited capacity, Operation Nanook. Thanks also to JTFN for being as open as they were and to the Public Affairs organization for their professionalism and assistance.

1. http://www.forces.gc.ca/en/operations-canada-north-america/index.page

2. http://www.forces.gc.ca/en/operations-regional-jtf-north/jtf-north.page

3. JTFN briefing, Maj. Conrad Schubert (J9 Civil Military Cooperation, JTFN), 232000 Aug 17, Rankin Inlet FOL

4. http://www.forces.gc.ca/en/operations-canada-north-america-recurring/op-nanook.page

5. JTFN briefing, Maj. Conrad Schubert (J9 Civil Military Cooperation, JTFN), 232000 (+19:30) Aug 17, Rankin Inlet FOL

6. interview, Cpl Heidi Schulz, 231200 (+00:45) Aug 17, Rankin Inlet FOL

7. interview, Cpl Heidi Schulz, 231200 (+04:40) Aug 17, Rankin Inlet FOL

8. JTFN briefing, Maj. Conrad Schubert (J9 Civil Military Cooperation, JTFN), 232000 (+32:20) Aug 17, Rankin Inlet FOL

Figures 1, 2, 3 – presentation Joint Task Force North: Collaboration to Achieve National Aims in the North, presented by Maj. Conrad Schubert, (J9 Civil Military Cooperation, JTFN), 23 Aug. 2017.

Figure 17 – C-19 Ranger Rifle, South Manitoba Rifle, http://www.southmanitobarifles.com/forums/viewtopic.php?f=1&t=272

All other figures courtesy Richard Lawrence Photography.